Oppenheimer

The tradition of the biopic is fairly commonplace: we watch a man (usually) rise to great heights before suffering a tremendous fall. But what happens to the biopic when with that man falls all of mankind? How do you approach the life of a man who made the death of millions in a blink possible? What do you do with the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who in some ways started, changed, or ended modern history?

It's a mighty task for any filmmaker, not only to try to capture the gravitas of that impact, but also to avoid the typical schmaltz of the biopic, a genre overburdened with cliche. There are so many conventions to the biopic that making one without any is like trying to pass through a minefield unscathed. So perhaps the only solution is that the filmmaker who takes on the job must have such a strong identity, their own bag of tricks, their own arsenal of conventions that they can overpower the weight of the biopic with their own style.

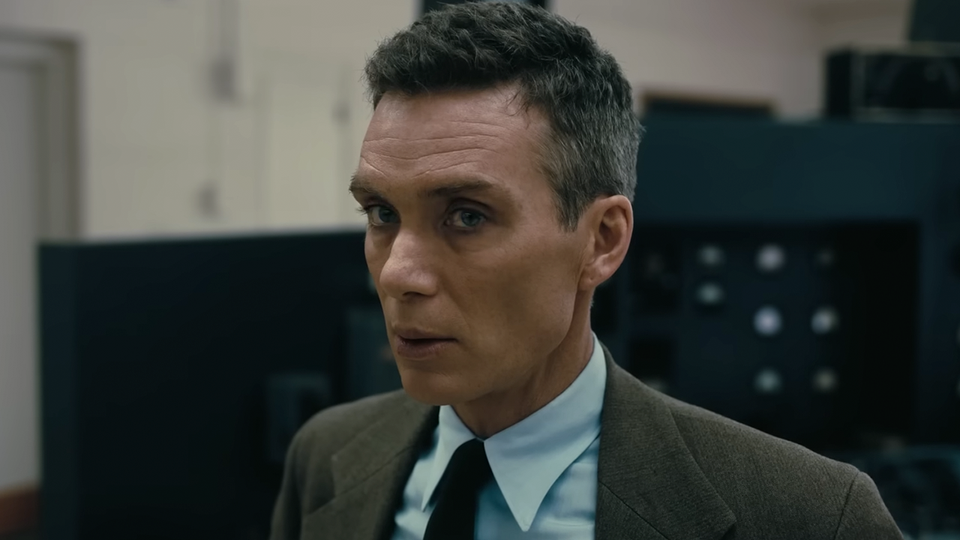

One such filmmaker is Christopher Nolan, writer/director of "Oppenheimer." Over his many films, Nolan has demonstrated his multitude of idiosyncrasies which sometimes support and sometimes hinder his storytelling. Achronological storytelling raised the stakes in "Dunkirk" but made "Tenet" incomprehensible. An intense and immersive sound design in "Inception" made for unintelligible dialogue in "The Dark Knight Rises". Sharp practical visual effects in "Inception" and "Interstellar" made for spectacle, with little emotional substance. And across all films is a specific kind of coldness, a detachment from the material in front of him. Like the Batman of his Dark Knight trilogy, Nolan seems to prefer standing above the rabble, observing, presenting, and never quite inviting. This distance makes for very tense sequences and cerebrally complex plots, without possessing much emotional weight. That has always kept me at a distance from his films, as I can enjoy his films intellectually and visually, but not necessarily feel moved by them.

But in "Oppenheimer," that deficiency becomes Nolan's strength. Because like Nolan, Oppenheimer is detached from his world, lost in theory. He attempts to distance himself from politics, standing away from the push and pull of the people, and immerse himself in physics. He does not think about the consequences of the bomb until it whips his face with its wind. Nolan's detachment this time does not separate us from the characters; instead it pulls us into the psyche of J. Robert Oppenheimer. And as that psyche begins to falter, so do we with it.

That is one of the most essential things to understand about this film. It isn't attempting to present an objective or historical truth of the creation of the atomic bomb. It is designed to be a subjective perspective of its birth by its father. And that means the film is fraught with his same blindness and biases. There are many well-founded criticisms of the film online for its purported misogyny, racism, and historical erasure. But those are all in-line with the figure of Oppenheimer himself, a chauvinistic philanderer with nary a moral backbone. I would agree with these criticisms more heartily if the film valorized the man, if it suggested his behaviour is worth emulating. But if anything, the film is about the consequences of his flaws and failures. There is nothing heroic about Oppenheimer, nor the bomb. We are reminded ad nauseum of how the bomb was largely an American show-of-force to the Soviets, with the Japanese as test subjects for history's most powerful weapon. The film depicts increasingly disturbing scenes of the American military, salivating for communist blood whether it spills in Moscow or in the court room next door. Understandably, the criticisms of the film's omissions may compromise many audience's emotional experiences of the film. They may find those gaps too glaring to remain invested, too disgusted to care. But they are there by design.

And for me, that design worked. Nolan's movies have never looked, sounded, or felt better than "Oppenheimer." It is the culmination of so much of his prior work, with a deft control of the film's multiple timelines, an incredible score and sound design, groundbreaking visuals that connect directly to the film's themes, and a ratcheting intensity as the timer takes down. In prior films, his idiosyncracies always came with a drawback. But in "Oppenheimer," each of them cohere into a grand vision of violence.

My largest qualm with the movie, barring the earlier criticisms, is that while all of its filmic elements align, the dialogue in its script is at times overwrought. Nolan's penchant for the callback is too heavy-handed and often distracts from the film's core action. It's also particularly noticeable here because of how eloquently Nolan create visual symmetry across the film. The patter of rain onto a window lands so much sharper than a clumsy line said twice. Those visual rhymes are far more engaging than a rote line repeated, and at times compromises the performances from an otherwise stellar cast.

This is Nolan's biggest star cast yet, with many historical figures rotating around the orbit of J. Robert Oppenheimer. While they all blend into the same sphere of paranoia and complicity, they each add their own flavour of original sin to the mix. Robert Downey Jr. turns in a career best performance as the prideful Lewis Strauss; Benny Safdie hungers as scientist Edward Teller; Florence Pugh's Jean Tatlock seeks her own brand of convert. They make the film more than just the story of the bomb that changed the world, or the man who could never forgive himself for its creation. They make it about the nation that enabled that act of destruction and thrust the world into the atomic era. It's a biopic in the way only Nolan can make it. It's a biopic about Oppenheimer. And the bomb. And the world that changed with it on July 16, 1945.