Asteroid City

In Wes Anderson's prior film, "The French Dispatch," the auteur writer-director took audiences through an exploration of multimedia. There was animation, there was modern art, there was newspapers, and in one of my favorite sequences, the theater. In that scene, a cast of young actors recreate a section of the plot that, within the film's world, was adapted by a playwright and staged on the West End. It was one of many idiosyncratic framing devices within "The French Dispatch," from an artist whose work is already abundant with idiosyncrasies.

Those go far beyond the list of facile aesthetic choices that TikTokers or Instagrammers have been using of late to ape his style. It is not merely symmetry or pastel colors. It's an obsessive attention to visual detail, laser-focused dialogue, and production designs so intricate that the viewer has to ask, "how did they do that?" that make Wes Anderson Wes Anderson. What you see on the screen is only an entryway; Anderson's real obsession is not with a wallpaper's soothing pink or a meticulously laid-out plate of fine dining, but instead with the act of making art itself.

In his latest feature, "Asteroid City," artmaking dominates the film. He returns to the device of the theater of "The French Dispatch," but takes it one step further. "Asteroid City" is a TV broadcast of a stage production, that itself is a retelling of the creation of the original play "Asteroid City." We are four levels deep here, with actors playing actors playing actors, making for a fascinating, form-challenging device. Though it is thought provoking, that same device does block some of the emotion from the film's plot (the innermost plot of the play, "Asteroid City"). And as the film goes on, cutting in and out of play, TV broadcast, rehearsal room, I started to wonder if this was purely an intellectual exercise from Anderson, an opportunity for him to play with form without grounding it in the film's story. But as the film approached its zenith, my doubt was cast aside in a singularly transcendent moment that had everything falling into place.

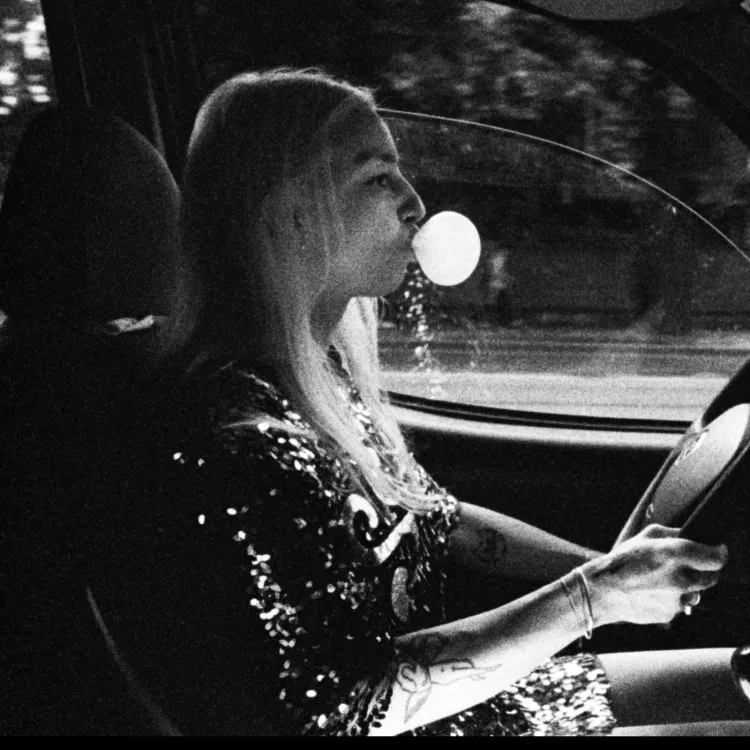

The cast of characters in this film is enormous, even by Wes Anderson's standards. The core of the film surrounds Jason Schwartzman, as actor Jones Hall, as the character, Augie Steenbeck, war photographer and recently widowed father of three, taking his family out to Asteroid City for the annual Junior Stargazer convention. There, he meets Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a Hollywood starlet, General Gibson (Jeffrey Wright), the stolid commander of the nearby military base, Dr. Hickenlooper (Tilda Swinton), the excitable head researcher at Asteroid City, and a cavalcade of other families with their own little prodigies in tow. Many of the actors are veterans of Wes Anderson's oeuvre, fluent in his style of under-emotive characters and razor-sharp wit. Schwartzman himself has worked with the director for 25 years, appearing in his sophomore film, "Rushmore." But one of the most joyful additions to Wes Anderson's regular ensemble is Jeffrey Wright, an actor with just the right balance of gravitas, aplomb, whimsy, and pathos for Anderson's script. Other welcome additions include Hong Chau and Margot Robbie, each only in the film for a scarce few minutes, but whose impact are felt long after they exit stage right.

Anderson's scripts are not about speed, though the characters speak extremely quickly. Nor is it about tone, as for most of the movie the characters speak in monotone. For the right actor, it is about burying the years of hurt each character carries beneath their words, even as the lines go by swiftly and flatly. This could even be described as an act of subterfuge, each line a Trojan horse designed to lower our defenses with a deep current of emotion underneath.

That same sleight of hand occurs within the film's framing. As mentioned, the early sections of this film are undoubtedly entertaining, both visually spectacular and outright funny. But each time we cut between the TV broadcast and the script of "Asteroid City," I felt pushed out of the film's story. It becomes difficult to know where to invest your emotions into, as the film is constantly reminding you that it's playing a trick. Each section of the play starts with a title card informing us of the Act and Scene number. Though it has its charm, it's a disorienting device that has audiences constantly aware of the film's framing, so obtuse it is almost frustrating. But I forgot all of my complaints when Anderson inevitably shows his hand. It's an incomparable moment that lands precisely because of Anderson's militant commitment to withholding emotion, or at least emotion as we are accustomed to seeing it. It's a collapse of form as theater and film meet, so delicately that it only hit me with its full impact hours after I had finished the film.

Both the cinema and the theater share the beauty of the temporary: we enter a physical space together and we are moved, not just by what we see before us but by the memories the art conjures up. The actors recall and the audience remembers. And then when it's over, actor and audience alike return to their lives, this experience another memory to add to their vaults. "Asteroid City" is about the temporary, the fleeting moments that whisk by us before we can hold onto them proper. Steenbeck can snap a photograph but he cannot become the person who took those photos again. He can advance the roll and take another. He can't reverse it. The best he can do is look at the photo, recall the dialogue he did say, or think of the lines he should have said. The curtains have closed on Augie Steenbeck. But Jones Hall lives past the stage, past the broadcast, past Asteroid City. And so the play stops, but it never actually ends.