Promising Young Woman - Warning: spoilers and references to sexual assault

In Promising Young Woman's opening scene, Cassie, played by Carey Mulligan, is passed out, inebriated in a bar. Two men eye her, while the third man calls her a taxi to bring her home. The third man, played with the right amount of slime by Adam Brody, reveals himself as much as a creep as the two oglers, trying to bring Cassie into bed.

At this point, I ask myself. Are we starting with a direct onscreen depiction of sexual assault less than 5 minutes in?

But right before Brody can make his move, Cassie speaks. She repeats her question to him, earlier filled with confusion and despondency, now fully conscious and tinged with a threat.

"What are you doing Jerry?"

And just like that, the power is reversed.

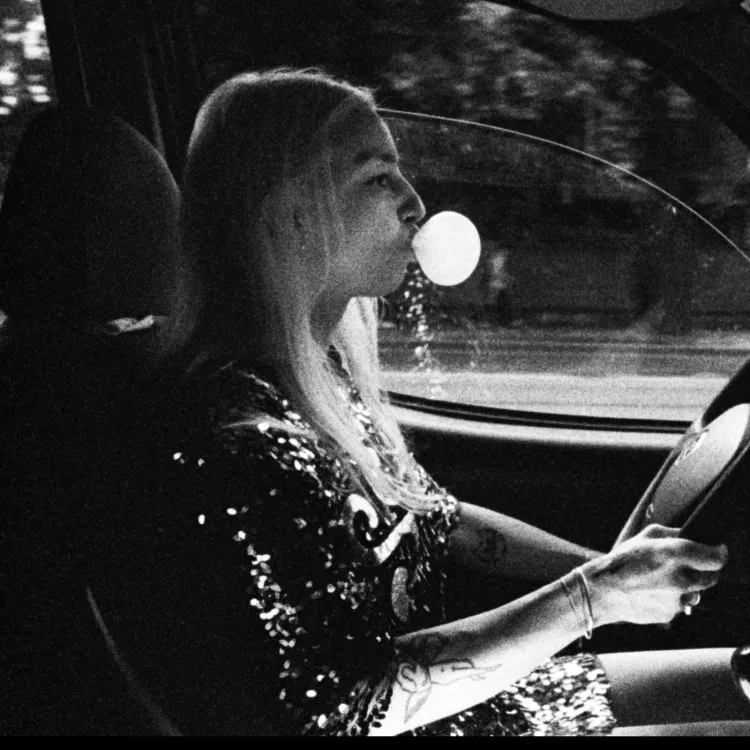

It's in these reversals that Promising Young Woman is most exciting, when Cassie is in such thorough control of herself, the filthy men around her, and the camera. Cass in a sense spends the first half of Promising Young Woman as its director, creating cues, writing lines, staging events, to get what she wants.

And there's something deeply satisfying about watching Cass get her way. It's an inversion of the male-centric revenge genre, where a man is spurred into action, typically by the death of a woman. Cass is still moved by the death of a woman, but the woman is not her innocent daughter or a down-and-out sex worker. She was Cass' best friend who fell into a deep depression after a sexual assault. And instead of turning to gun slinging or bone cracking, Cass ruins her targets emotionally, leaving them fully aware of how close they are to the edge. Just a little push, and their lives are over, just like hers.

There's a swiftness and clarity to these early sections of the film, when the film acknowledges Cass' actions are questionable, but doesn't get bogged down in big moral conundrums. But, almost in a bout turn halfway through, the film turns on its head, deciding it's time to get serious.

The film was not really a comedy before this. There's comedic bits, particularly from Bo Burnham, excellently cast (and probably two performances away from an Oscar). Yet there still was a wilfulness and a sense of play, like when Cass, with a single unflinching glare, turns the catcalls of construction workers into insults, then into expressions of raw fear and discomfort.

But now, when the movie changes tone, Cass is no longer director. She's now an audience member, watching the lawyer she aimed to destroy, collapse into tears before her, waiting for his day of judgement after years of guilt. She's told to move on by her best friend's mother, to bury this hatchet, and live her best life. Both scenes are great concepts in theory, but in execution, come off as incredible rushed and unearned. They're presented as lessons to Cass from the filmmaker, to give Cass enough reason to leave her bloodlust behind so the movie can then inevitably drag her back to her life of violence. The screenwriter becomes everpresent, taking the reins from Cass and her motivations, to orchestrate events simply because they're supposed to happen. We lose track of this tight character drama, and end up with clunky scenes, driven by necessity.

All of this culminates in the film's most disturbing scene, and arguably one of the most visceral scenes I've seen in recent memory, where Cass, while trying to disfigure the man who assaulted her friend, is suffocated by this same man, pressing his knee into a pillow over her face. It's a brutal long-take as we watch this man weep, as Cass' legs stop twitching.

I absolutely hate this scene.

It is not the artist's job to make audiences comfortable. There's the Banksy quote that art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable. I accept that filmmakers have every right to disturb me, especially as a man watching a film about the female experience. Yet the decision to connect Cass' murder and sexual assault in both a visual and auditory way felt like Fennell was determined to twist the knife, to prove a point about the vicious daily reality women face, without considering it within the larger context of her film.

To be clear, the lesson itself is not the problem. It's the delivery of this message, which stands in such contrast to the cathartic joy of Cass' power earlier in the film, and is only made more unpalatable by how the film chooses to follow Cass' death.

During my viewing, I had misgivings about Cass' grisly demise but was willing to see where Fennell would take the plot. But, rather than dwelling on this cruel act, Promising Young Woman dives into, what can only be described as, a screwball comedy as the murderer and his best man attempt to dispose of the body. Forcing an audience to endure the prior scene is one thing, but the lack of breathing room had me questioning why the movie was still going, now that our protagonist, the only character we have come to empathise with, is gone. The point has been made, so why continue showing us how Cass suffers, even after her death?

And then comes the twist, that Cass already saw her death coming. She left behind evidence that leads to her murderer's arrest at his wedding, cued by scheduled text messages from her beyond the grave. Her final text? A winking smiley, as if to say, ah ha! Now I've caught you.

The entire ending struck me as Fennel trying to have her cake and eat it too, both delivering a grim and harsh look at Cass' path, and also a neat, happy ending, tying up all the loose ends. But by bringing these two together, the ending fails to deliver on both parts. It is neither sobering nor comforting. Instead it is a muddled mess of a message, that cheapens all the incredible character work that preceded it.

I don't like to dwell on a movie's politics. We should be assessing craft and delivery, more than the message itself. Because if we approach films, hoping they will align with our idiosyncratic perspectives on the world, we would find most of them not to our liking. But when a film like Promising Young Women forsakes it's complexity and its characters for its message, I have to contend with what it's saying. And in this case, the lesson is contradictory and incoherent, suggesting Cass' sacrifice was both necessary and rewarding. It's an incredibly disappointing conclusion, much more in line with traditional revenge movies, in a film that managed to challenge most aspects of the genre.

Promising Young Woman, in its early parts, is a fantastic character study, anchored by Mulligan's controlled and precise performance. Mulligan captures that singular drive of Cass, orchestrating events behind a fake smile and false apathy, as her vengeance consumes her whole. But by the ending of the film, Cass is no longer the director. Instead, she is a prop in a parable, completely deprived of any agency. Gone is the angry, complex, mournful Cass that we grew to understand. And all we're left with is a winking smiley.