Poor Things

Yorgos Lanthimos has a penchant for the odd. The director loves to sit in strange places, not just physically but socially; in the two Lanthimos films I've seen ("The Lobster" and "The Favorite"), there's a sense of a parallel social structure, a world with its own norms, its own form of conversation, its own absurdity. And in both those films, the characters are trapped in that societal ludicrousness. There is claustrophobia, oppression, bleakness, weirdness that restricts and restrains its characters.

That would sound true on paper for his newest film, "Poor Things." The film follows Bella Baxter (Emma Stone) cobbled together by a surgeon, Godwin Baxter (Willem Defoe), himself experimented on by his cruel father. Godwin keeps Bella within the confines of his odd home, to save her from the cruelty of the world, but she insists on venturing into it, surrounded by cynics, brothels, etiquette, unwelcome wedding proposals, and an unrelenting patriarchy that demands her submission. But Bella is not trapped. Instead, Lanthimos ruptures the cage through Bella, who, rather than being pressed in by the world, rails against it. She is the one person who can see through the bars, recognizes the trappings, and wants to make something better. The weirdness in this film, like with Lanthimos' other work, comes from its exaggerations of our social conventions. But here, rather than have a character suffer through it, Lanthimos and screenwriter, Tony McNamara, have Bella point at the world, at our world, at her world, and say, "isn't that ridiculous?"

Stone creates a whole world through Bella Baxter, making the unreal real. She's tasked with depicting not just Bella's narrative journey, but her mental development, going from infancy into adulthood, all while in the same body. The disjunct between Bella's adult body and infant brain make for terrific comedy in the film's early scenes but as the film develops, we become almost as enthralled as the other characters with what she becomes. It's especially entertaining set against the downfall of Mark Rufallo's character, Duncan Wedderburn, a conniving scoundrel of a lawyer, who warns Bella not to fall in love with him. While Bella matures, Wedderburn descends into a pitiful wastrel. She sees through the snare Wedderburn has laid for her, and he instead become stuck in a web of his own making.

Part of why this film feels so freeing is its visuals, which like its characters, is adjacent to our reality. Every shot of the city, the sky, or the sea is incredibly beautiful, soaked with color. It feels like everything, especially the outfits, are bursting with visual vibrancy, making the film a joy to watch even without its story thanks to the art direction of Shona Heath and production design of James Price. Its style is not empty flavor either, as the oddness of the film's visuals and cinematography further its themes.

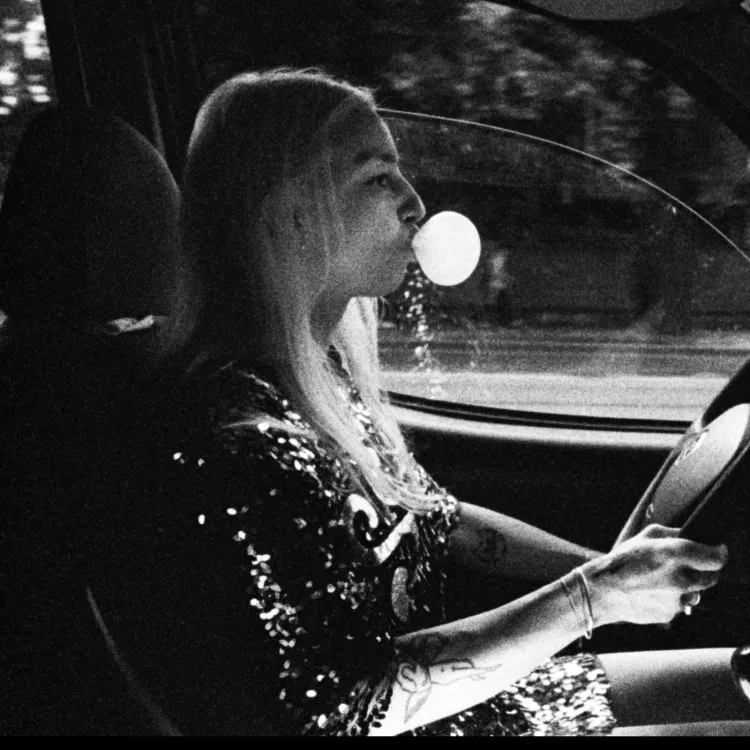

There's the simple reading, with its black-and-white first section; Like Dorothy, Bella only sees color once she wanders into freedom. But there's more to it than color, as Lanthimos uses disorienting perspectives to destabilize audiences throughout the film. It makes the first section feel extra uneasy, as the frame often represents a distorted reality, more akin to Godwin's worldview. And finally, the film's select deployment of a pinhole perspective points to the only characters acrually trapped in "Poor Things." Despite everyone's best efforts, Bella cannot be contained. And the men who try to hold her end up encountering the limits of their own masculine worldview. They come up against the edges of their control, stuck in a tiny circle, railing against Bella. The weirdness of its visuals aligns with the weirdness of its world, both working towards freedom rather than oppression. It's the most united of Lanthimos' work, and his most earnest work, evading cynicism at every turn. The only moment when I felt it slipping away from me was in its final quarter, when it felt like it took one more narrative move than necessary. But ultimately, I was won over anyway and by its ending, was surprisingly moved by this film about stomach acid, mutilation, and earlobes. It's a far cry from the cynicism of "The Lobster," or the machinations of "The Favorite." It's a heartfelt turn from Lanthimos, and I look forward to seeing what strange world he and his team conjure next.