Triangle of Sadness

In the last eight months, I've seen multiple settings in films work as microcosms of the ultra-rich and as metaphors for the hierarchical class-based society we find ourselves in. There's been a sex cult on a resort island in “Infinity Pool,” an exclusive fine dining restaurant in “The Menu,” and a glorified game of tag in a mansion in “Bodies Bodies Bodies.” But none of these films have gone as far as to have three distinct metaphors coincide within their movie, like Ruben Östlund’s "Triangle of Sadness," a dissection of materialist society across catwalks, yachts, and a third location I won't spoil. It's a sprawling movie about ownership and property, often hilarious, but at times, perhaps casts a net too wide for its own good.

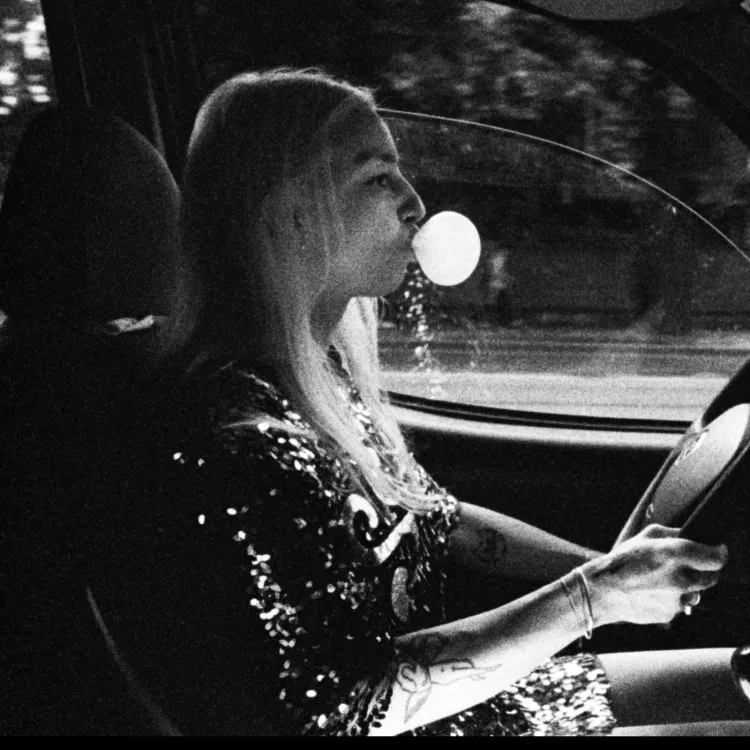

Ostensibly the main character of "Triangle of Sadness" is Carl, a chiseled, angular male model, played by Harris Dickinson. Carl is more of a vehicle for us to move through the film's different locales, to take us through the thorough detachment of the grimy 1%. That isn’t to say Carl possesses no character. Instead, he is a terrible character, terrible in that he's so strong and lived in, that he's intensely unlikable especially as he competes with his girlfriend Yaya (Charlbi Dean Kriek) for the title of most deluded. It does make for a frustrating viewing experience, watching these two stumble through manipulating each other. That frustration though is really a testament to their excellent, if not irritating, performances. Everyone knows a self-righteous Carl or an obnoxious Yaya in their lives or at the very least, some watered-down version of the two.

These two are nothing compared to the film’s actual wealthy characters sickening in their indulgences and apathy. Östlund doesn't take this to the same psychosexual or outright psychopathic heights as Mark Mylod does in “The Menu” or as Brandon Cronenberg does in “Infinity Pool.” Instead, Östlund's ultra-wealthy are so grotesque because of how real they are. They are of course heightened for comedic effect at times such as the geriatric couple stating how their love got them through the economic difficulties imposed by a UN ban on the production and sale of landmines. But there's also the very real heart to it, an uncanny authenticity to their obnoxiousness, like the Russian oligarch's wife demanding a crew member join her in the pool “to enjoy the moment.” These moments are both intensely infuriating and funny for their razor-edged truth.

The film is not merely about subjecting us to our own reality in more direct, repugnant ways. Östlund possesses an almost sadistic intent with this film, showing us the worst these people have to offer before subjecting them to utter disgrace and humiliation. For some, this cosmic punishment may be overbearing, particularly with its focus on fluids and fecal matter. But for others, there is a grotesque catharsis to it, to see these characters suffer in a way we will likely never see in our lifetime.

There is a fantastic turn in the film's third act, where the story’s reins are handed to Abigail, one of the yacht's Filipino cleaners, in a star-turn by Dolly De Leon. De Leon is excellent in the role, navigating the character’s conflicting motivations and newfound power as the world as she understood it flips on its head. It's this shift that elevates "Triangle of Sadness" over other depictions of class as it brings together otherwise neglected intersections. It goes beyond a facile critique and brings it into more complicated territory, especially with the film's ending. While this final third does deepen the film’s themes, it also feels like it drags. It lumbers along slowly and possesses its own narrative structure, almost separate from the rest of the film.

You have to enter this film not wanting to bridge its three chapters; instead, treat them as three roughly connected short films conjoined by a shared cast of characters. It makes some of the film's tonal shifts easier to stomach, though you have to be willing to go on that ride.

At times, “Triangle of Sadness” strikes me as more a manifesto or a declaration, than a story-driven film. Surprisingly, those are my favorite moments. Perhaps it is because they are the most inherently joyful, almost as if you can hear Östlund giggling off-camera. These polemics are when it feels like he holds nothing back, unencumbered by the weight of Carl or Yaya. One such scene is a drunken war of quotations, lobbed back and forth between the yacht’s Marxist captain (Woody Harrelson) and a Russian literal shit-peddling oligarch (Zlatko Burić). There is a raucous energy to this barrage of citations from Reagan, Marx, Mao, and Thatcher, that reminds us what this film is really about. It's about collision. It's about an impending crash between worlds, one that the Cold War never completed. Because if we are to take this deluge of silver screen spins on society as a sign of anything, it is that we are approaching a tipping point. But what we must ask ourselves is if these movies are the path to a more equitable future, or if they are simply an opiate of the masses, balms to soothe the burns we cannot heal.