Licorice Pizza

Paul Thomas Anderson tells movies like they're novels. And I don't mean classic novels like Pride and Prejudice or Frankenstein. I mean sprawling, post-modern novels, where characters appear, disappear, events from real life occur, fictional things happen, circumstance and coincidence hold random weight, and often, a character knows someone real, without being real themselves. They feel like tapestries of short stories, sometimes stitched together without their respective endings.

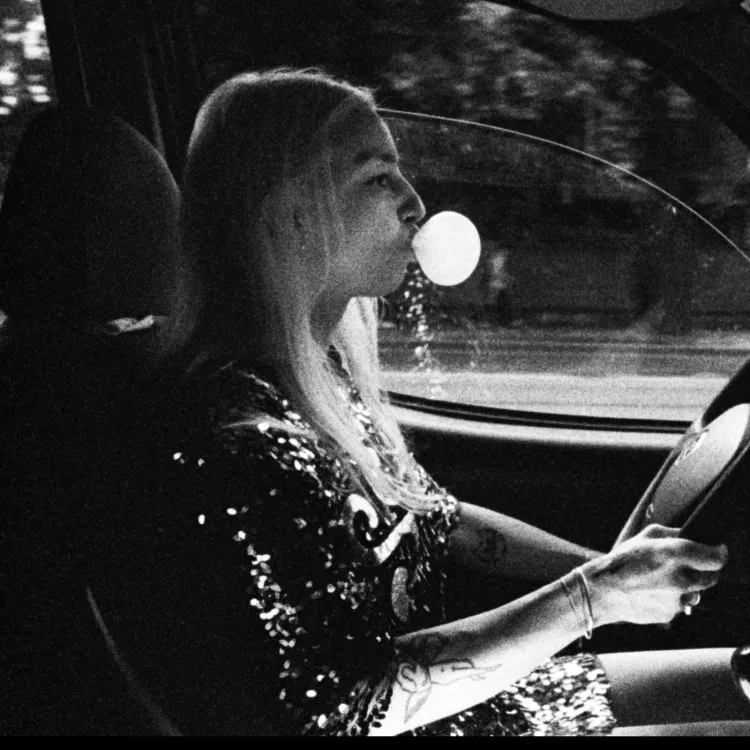

That's why "Licorice Pizza", in particular, feels real. It's not because the 1987 oil crisis, a real event, impacts the plot. It feels real because it feels like it was lived, with stories that bleed together in the way that the days of summer vacations do. It feels like we are watching Cooper Hoffman's Gary Valentine and Alana Haim's Alana Kane meander through days before us. They are flawed, they are messy, they are clumsy, and most importantly, they are young.

Age has become a central part of the internet conversation surrounding "Licorice Pizza", namely the age gap between Alana and Gary. Without spreading slander, a lot of that discourse appears to have come from people who have not watched the movie. Because the movie is well aware of the age gap. It's one of the first things Alana points out to Gary. But, to be charitable to its detractors, awareness doesn't mean innocence, if a movie can be guilty of anything. Guilty, in this case, of endorsing the ten-year age gap between its protagonists. And I'll say this: it isn't endorsing it. Nor is it critiquing it. The age gap is simply there.

Which has me asking myself, do we need our movies to be the moral arbiters of society? Do we need our films to wear their moral stances on their sleeves? Do we need our characters to be morally virtuous? Despite my tone, I don't think there is a one-size-fits-all answer to these questions. On certain topics, we're going to need our movies to be direct. War movies have to hate war. Slavery movies have to hate slavery. Our superheroes have to, at some level, be good.

But "Licorice Pizza" is a movie about people, not heroes. It isn't a fable that's trying to teach you anything. Nor is it an argument trying to convince you. It's about two out-of-place kids, living in the '70s, emphasis on living.

Some movies are lauded for their ability to recreate a specific time in history.

Most recently, Quentin Tarantino was regaled for his picturesque version of 1969 Los Angeles in "Once Upon A Time In Hollywood...". That movie was a treat for people who understood the context of that time period, the headlines Tarantino invoked, the Hollywood stars re-represented.

That movie was not a movie for me. I know little about the idealized version of Hollywood Tarantino created, and for that reason, the many comparisons between "Licorice Pizza" and that film had me hesitant.

Paul Thomas Anderson's Los Angeles welcomed me right in. I wasn't boxed out by references that flew over my head. Everything was right in context, and I'd feel the same without knowing who Barbra Streisand is. That's because we have two incredibly well-lived vehicles to take us through this world: Gary and Alana. If this film had to be compared to another, Greta Gerwig's "Lady Bird" is a much better choice, where the titular Lady Bird is our entry point into '90s Sacramento.

Perhaps teenage protagonists also make for more immersive time-capsule stories. Because when you're a teenager, you don't fully understand or fit into the world around you. Even Gary Valentine, the mini-mogul that he is, is a fish out of water, despite his best efforts. It's Gary's constant displacement that had me so endeared to him. Sometimes, he is a little boy, trying to wear a big man's suit. Other times, he's an overgrown teenager literally performing as a small child. Sometimes, we get glimpses into his actual teenage self — sex-obsessed, juvenile, immature. But most of the time? Gary is pretending to be an age other than his own.

I'd also be lying if I didn't admit that half the time I couldn't stop thinking how much Cooper Hoffman looks like his father, Philip Seymour Hoffman. Don't get me wrong, Cooper Hoffman is more than up to the role. But the casting does lend an additional layer of youth and ageing, when we watch Cooper Hoffman, and think about his father, who tragically is no longer with us.

Alana Haim is fantastic. She's hilarious and heartbreaking as Alana Kane, the 25-year-old woman stuck helping high school kids comb their hair for their yearbook photos. Like Gary, Alana is out of place. She knows what her age is, but she isn't where she wants to be. She's directionless, which isn't helped by her stifling household. Nor is it made better by the bevy of bad guys around her, all treating her as a replaceable object. Except for Gary.

And that takes us back to the age gap question. But that's also why it doesn't matter. "Licorice Pizza" is about maturity and immaturity. It isn't about whether Gary is right for Alana or vice versa. They see in each other what they need at that moment. In Alana, Gary sees a woman who can handle the oddness of his years, both high and low at once. In Gary, Alana has a boy who reminds her that her opportunities are endless.

Does that mean they stay together forever? That they'll have a happy marriage? They'll have three kids and it'll all work out? I don't know, and I don't care! There is romance in the movie, but it isn't a romantic movie. It's really a snapshot into one summer, crammed with waterbeds, movie stars, mayoral candidates, and a drunken Bradley Cooper. Alana and Gary make mistakes, they fight, they argue, they laugh, they do weird things, they make questionable choices (Gary especially). But they're young and it's the summertime. There's no rush to get it right. There's no need to end their story with a lesson.