Kimi

Someone complained to me the other day about how there is hardly any art about COVID. Specifically, there are very few feature-length films, that even without being necessarily about COVID-19, even mention the pandemic at all. The problem is film as a medium takes time to develop, script, produce, edit, before we get to see the final product. We have been in a pandemic for two years now, and most full-length films need longer than that in the oven to be ready for consumption.

Enter Steven Soderbergh.

Steven Soderbergh, who wrote three scripts in quarantine.

Steven Soderbergh, who shot two movies ("Unsane" AND "High Flying Bird") entirely on an iPhone, just because he could.

Steven Soderbergh, who has directed a movie, sometimes two, every year since 2001. His only break? 2015-2018, when he was instead directing and producing 20 episodes of “The Knick”, and producing two other television shows.

Steven Soderbergh, who directed “Contagion”, a film from 2011 that predicted much of COVID-19’s spread and global effect.

If anyone was going to be the first to make a movie with COVID-19, it would be Steven Soderbergh.

But speed isn't enough. Some artists are choosing not to feature COVID-19 in their work, because it would swallow the rest of their movie. The elephant in the room ends up being the only thing you can actually see in the room. And if the elephant is there, you are going to have to say something about it. You have to give your take, your stance, but what stance does anyone want to give on a rapidly evolving disease? It's the same as any art about the "current situation" — by the time your work is out, it's likely your exploration is already outdated.

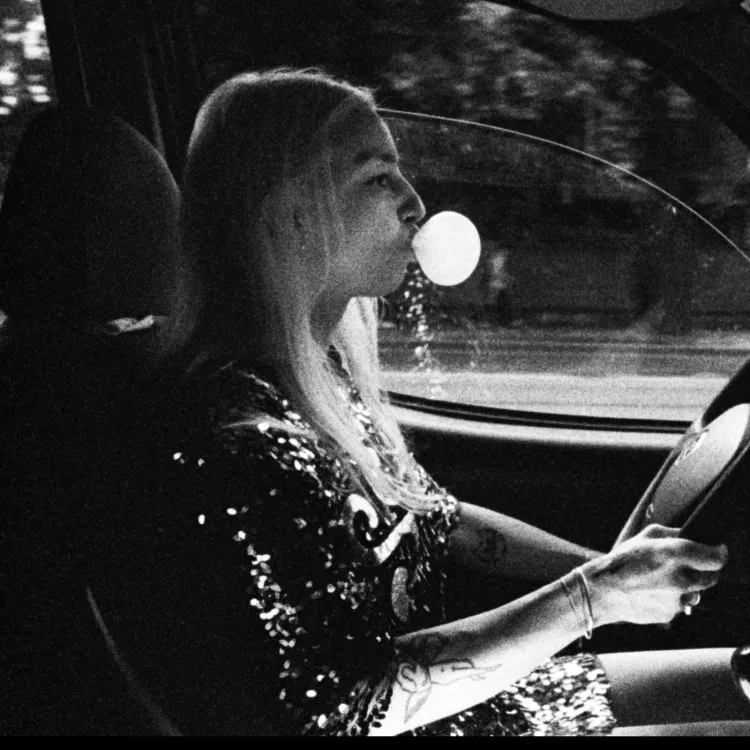

Which is why it's so impressive that Soderbergh's latest release, "Kimi", takes place in the current era, including the pandemic, and somehow avoids being about the pandemic. COVID-19 is there, but it's in the background. It's part of the setting, it influences the characters, but it doesn't suck up all the air. It undoubtedly affects the protagonist, Angela played by Zoe Kravitz, and her agoraphobia. But it's only part of the picture.

Because if "Kimi" was actually about any contemporary issue, it wouldn't be COVID-19. It would be about surveillance.

Plenty of reviewers are calling "Kimi" the “Rear Window” of the modern age. “Rear Window” is an Alfred Hitchcock classic about an injured man, bound to his window, who witnesses a murder. “Rear Window” is also from 1954. There wasn't a box in your room listening to your conversations, nor was there a portable computer in your pocket that is tracked and traced.

The central conceit of "Kimi" is that agoraphobic Angela works from her apartment as a human receiver of voice commands delivered to Kimi, this world's version of Siri, Alexa, or Google Home. Her job is to sift through the instructions Kimi doesn't understand and update the code so that Kimi's vocabulary expands to recognize colloquialisms, slang, vulgarities. And then Angela hears something she shouldn't.

That's the “who” of "Kimi". But I would say Soderbergh is much more concerned with the “when”, and the “where” of his film. The "when" we've already discussed: It's during a pandemic. But the "where", the literal location of "Kimi", is more important to its plot. Angela, an employee of Amygdala, a booming tech company has moved to the USA's leading city in brain gain: Seattle. The not-so-shocking side-effects of brain gain are gentrification and rising homelessness, both of which feature in this film. Soderbergh doesn't stop to preach about these issues. Instead, these elements exist, sometimes in the foreground, sometimes more subtly. Like, Angela's apartment. When the protagonist's career is compared to the size of their apartment, most movies in New York end up more unrealistic than “Avengers: Infinity War”. But in "Kimi", Angela's apartment is thematically relevant to the concerns of the movie.

And that speaks to Soderbergh's most consistent trait, other than his speed: his efficiency. Each element of the film is utilized to further its story. The sound design is impeccable, a constant reminder of how much noise we are constantly barraged in, both in and out of our homes. The cinematography alternates between highly focused and shaky, putting us in Angela's mindset without actually being dizzying. Every shot is visually interesting, adding something to the narrative, whether it's the tidiness of Angela's apartment, how daunting a staircase can be, or a precarious kombucha bottle sitting at the edge of a counter. Despite the tenseness of its plot, I felt comfortable watching "Kimi", knowing that Soderbergh is in complete control.

But there are moments, particularly nearer the end where he loses the reins. We shift from the slow burn anxiety of the early sections of the film into a more action-oriented genre. It threw me off, having settled into an established rhythm. The fine control that has defined the rest of the film is lost, and we are racing to the finish. The plot demands a change, but it doesn't account for less finesse. And then it wraps up neatly, but maybe a little too neatly considering the film's themes.

But "Kimi" isn't looking to solve our problems. It's not even really trying to expose them. It's presenting information we already have, seamlessly stitched together within a tight 90 minutes. It's not going to change your mind, but that's not something it needs to do, much less, wants to do. So if you're looking for a well-made mystery, a character-driven story, some low-lying anxiety about the nature of modern surveillance, or a movie that is naturally present without forcing its Present-ness on you, then "Kimi" is the one to watch.