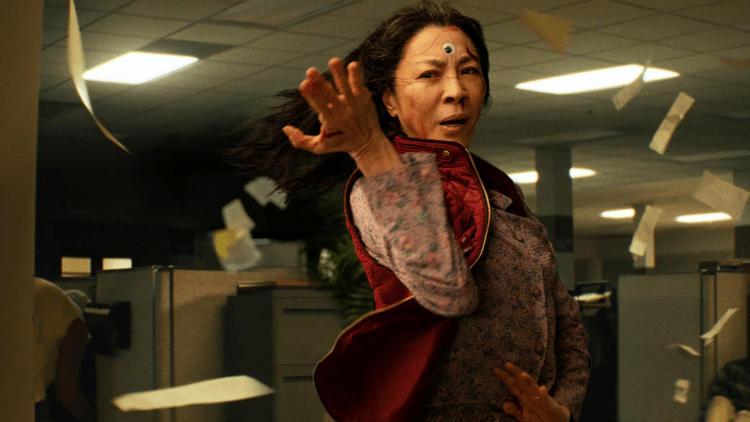

Everything Everywhere All At Once

When I was a grumpy teenager, I thought the best kind of laugh came from jokes that would make you feel bad for laughing later. The best comedies would masquerade as light and silly, before removing the mask to reveal the dark underbelly beneath. You laugh for a moment, but in the end, you must remember that the world is terrible, doomed, fatally flawed. Therefore, to me, the best comedies give you the illusion of escape before sticking a knife in your back between guffaws; twisting it to punish you for thinking anything in this tragic world could be funny.

When you’re a teenager, that’s what the world looks like. Shadowy; permanently overcast by a dark pallor smothering any semblance of hope. The only way a comedy can be good is if it actually is not a comedy and has in fact, been very very serious all along.

You laugh, then you cry. And then you cry more because you laughed.

Directing duo Daniels’ latest film, “Everything Everywhere All At Once,” will make you laugh and cry in the same breath. It will pull on your heartstrings with its googly eyes, its butt plugs, and its raccoons and extract from you both a laugh and a tear. And it is hellbent on not making you feel bad about it.

I cannot accurately describe the plot of “Everything Everywhere All At Once” plot to you. Or, I will not. Because you deserve to have this film’s outrageousness delivered to you blind. I will say, though, it fits perfectly, but also maturely, into the surprisingly well-trod path of multiverses, branching timelines, and infinite possibilities.

Despite being a relatively niche concept a decade ago, the multiverse is now a mainstay of the blockbuster. Spider-Man’s done it, Captain Kirk’s done it, Loki’s done it, The Doctor’s done it, Rick and Morty’s done it, Spider-Man’s done it again, and Doctor Strange is about to do a whole movie about it. But what none of these movies or characters have done with the multiverse, is be incredibly silly.

“Everything Everywhere All At Once” is silly. It is serious. And it is also very serious about being silly. It is committed to the idea of being silly. It’s silly in its cinematography, its editing, its costume department, its props, its killer sense of timing. But being silly doesn’t stop at a tonal choice; it is, importantly, a choice of perspective. It’s a choice by the characters and its creators, that when faced with the utter confusion of being alive, you can choose to be silly. In the face of existential despair, of a splintering society, an expanding listlessness, you can opt out of logic and choose the most illogical choice instead. You can choose to be kind.

Conceptually, “Everything Everywhere All At Once” could possibly spiral out and collapse under the weight of its own nonsense. But its three exceptional lead performances from Michelle Yeoh, Stephanie Hsu, and Ke Huy Quan, keep the concept in line. Being a film about the multiverse, each of them performs different versions of themselves. But rather than the shotgun smorgasbord of something like M. Night Shamalayan’s “Split,” this trio’s performances are anchored directly to their characters.

As Ke Huy Quan’s Waymond says near the start of the film, each of us is the sum of our littlest decisions. The accumulation of those little decisions over a lifetime makes us into who we are. That means the power of these actors’ performances comes not from the divide between the versions of the characters they play, but from the connection between these disparate selves, all aching for the same things. Ke Huy Quan shines especially bright in this regard; his Waymond Wang across the multiverse may be one of my favorite performances in film history.

As much as I love this film, I do chafe at the idea that it is a win for representation. Not that I don’t think it represents a specific community in a sincere and novel way. But I don’t think “wins” for representation matter anymore. How many supposedly gay, but also deliberately offscreen, characters has Disney gifted to us? What did “Crazy Rich Asians” do for my country, Singapore, beyond painting over it with a racially homogeneous brush? Representation means more than ticking a box.

“Everything Everywhere All At Once” is informed by the culture of its characters. That culture affects the characters, the setting, their worldview. But this isn’t an “Asian movie” — if that even exists. This isn’t a movie you ought to watch as an obligation to recognise Asian stories. This is a movie worth watching because it’s very good.

Reducing it to “Asian representation” ignores the particularities of this story. The Daniels aren’t trying to tell the quintessential Asian story; they’re telling the specific story of Evelyn, Waymond, and Joy. And by digging into the minutiae of this family, their history, their specifics, the small things of their lives become meaningful to everyone. It takes place in a particular somewhere, but it can land anywhere, and everywhere. When its narratives interweave, as its plots intersect, as its multiversal streams converge into the river in its final act, it will make you feel many things all at once.

The specificity of the emotional core of this movie, I think, is irrefutable. What I do have to admit though, is that its distinct brand of comedy may not be as hilarious for everyone. I laughed harder than I ever have in a cinema during more than one moment of this film — forcing me to name my favorite joke in this film would be like forcing me to choose between “Paddington 2” and cheese. But my sense of humor has also been broken by the bizarre idiosyncracies lodged in odd parts of the internet, the late-night hours of Adult Swim, or hours of juvenile sketch comedy. Not all its comedy is especially offbeat, but a few of its jokes may put some audiences out, though it definitely pulled me in.

Something else that may grind some audiences’ gears is that the film does not stop being silly. Even as the film approaches its climax, it commits to its bits. It returns to offshoot parallel universes that any other movie would have left as a one-off joke. The Daniels don’t return to these cosmic coincidences to make you feel bad for your earlier amusement. Instead, they let you continue laughing while finding joy in the most unlikely of places. At no point does this movie want you to feel bad for laughing.

During my second viewing of this movie (I can’t emphasize enough how much I loved it), I wondered what a universe would look like where “Everything Everywhere All At Once” came out during my surly teenage years. How my adolescent self would have received this movie. If I would have seen it as too goofy, too self-effacing, too sincere for my jaded, brooding self. If I would have found its jokes too crude, as the world was meant to be serious and not a bevy of orifice-centric jokes. If I would have spurned its simultaneous commitment to absurdity and its drive for catharsis, and wanted it to be either the salt or the caramel, not both at once. Or if my hardy shell would have melted under its relentless bombardment of nonsense, if it would have cracked through my veneer with its barrage of earnestness, if it would have made me make the illogical choice: to be kind, kind to others, kind to the world, kind to myself. Because there’s nothing sillier than that. To be confused, lost, disappointed, angry, but in spite of all that, to choose to be kind. I wonder what my alternate teenage self is doing right now, walking out of the cinema. And if, like me, he’s already thinking about who he should bring to watch it with him again.

--

This article first appeared in Fnews Magazine, edited by Nestor Kok.